Many Mexican-Americans growing up during the 1950s and ’60s had no awareness of Día de los Muertos. Due to the pressures of assimilation, relatively few Chicano families celebrated this ancient tradition, which combines elements of Christian and indigenous rituals. A new exhibit at the Oakland Museum of California, ¡El Movimiento Vivo! Chicano Roots of El Día de los Muertos, celebrates the resurrection of this holiday in the Fruitvale district and throughout California.

As the Museum celebrates the 25th anniversary of its Día de los Muertos ceremonies, this episode explores connections between the rise of the Chicano Power movement and surging interest in Day of the Dead. Listen now to hear Fruitvale History Project co-founder Annette Oropeza and Latino mental health pioneer Roberto Vargas share memories of how they came to embrace Día de los Muertos, their concerns about its growing mainstream recognition, and much more.

Do you want more East Bay Yesterday? Please donate to help keep this show alive: www.patreon.com/eastbayyesterday

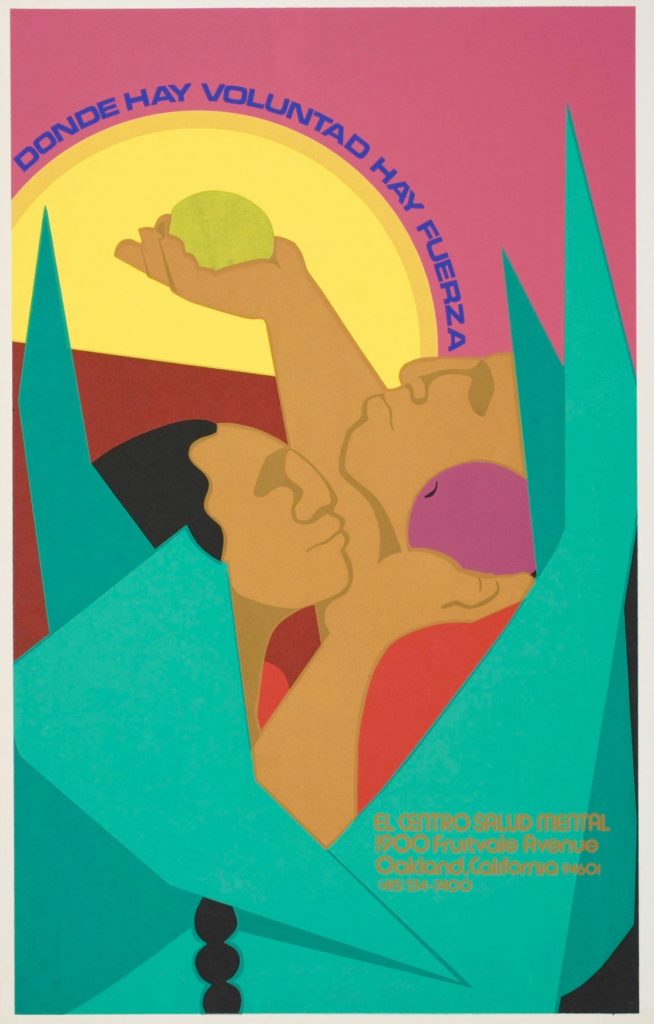

“Artist Manuel Hernandez Trujillo created this poster for a Chicano Liberation Conference at Merritt College. The Chicano Student Union planned this event as a follow-up to the national conference in Denver so activists in Oakland could tailor the national goals to local needs.” [Image: All of Us or None Archive, Gift of the Rossman Family. Caption: OMCA, ¡El Movimiento Vivo! Chicano Roots of El Día de los Muertos]

“This Cholo was first displayed at OMCA in 1984. In the early 1990s, he was met with strong reactions from The Amigos Group of the City of Oakland (a Latino advocacy group), who felt he represented a damaging caricature of Latino culture. In response, Tom Frye, former chief curator of history, organized a series of conversations with community members, museum staff and the artist — Richard Rios. The museum decided to remove the Cholo until more context could be included. Community members involved in these discussions formed the OMCA Latino Advisory Committee, which championed the first Día de los Muertos celebration here.” (Caption: OMCA, ¡El Movimiento Vivo! Chicano Roots of El Día de los Muertos)

East Bay Yesterday can’t exist with your support! If you enjoy the episode, please donate: www.patreon.com/eastbayyesterday