By Liam O’Donoghue / ORA photo captions by Moriah Ulinskas

Moriah Ulinskas is an archivist who has lived in West Oakland for two decades. For the past three years, she’s been organizing a collection of ~50,000 photographs taken by the Oakland Redevelopment Agency during the 1960s. The ORA’s vision for reshaping Oakland led to dozens of residential blocks being bulldozed and large stretches of downtown being flattened by wrecking balls.

Reflecting on this tumultuous era, Ulinskas told me, “Some people believe urban renewal programs were about the demolition of vacant or derelict neighborhoods, but I think when you look through these photos you see very active communities. The photos do a lot to break apart the story that these were neighborhoods that needed to be taken down.” However, Ulinskas doesn’t simply see the residents whose neighborhoods were devastated as passive victims. In her recent article “Imagining a Past Future: Photographs from the Oakland Redevelopment Agency,” she highlights examples of how community organizers built political power and engaged with city government in order to resist displacement.

She further complicates the traditional narrative by exploring the life of ORA director, John B. Williams, one of the first Black men to head a city agency, and an effective champion of affirmative action policies. “Williams was a bureaucrat, but he was also an ambitious urbanist,” Ulinskas wrote. “He believed in Oakland’s unique potential — in the city’s capacity to reshape itself into a 21st-century metropolis.”

February 9, 2019. [Photo: Liam O’Donoghue]

I interviewed Moriah Ulinskas for my KPFA radio program and you can listen to that conversation here (interview starts at 38-minute mark). However, since this is such a visual story, I’ve included below a selection of some of the ORA photographs* we discussed. Underneath each photo/caption (which originally appeared in Ulinskas’ Places Journal article), you can read some of Moriah’s thoughts on the corresponding photo. Below the ORA images, I’ve also included a few images related to this topic from the current “African American Oakland” exhibit at the Oakland Library’s History Room, which was curated by senior librarian Dorothy Lazard. [*The other segment of this episode covered the history of Moore Dry Dock Company, click here to see photos related to that story.]

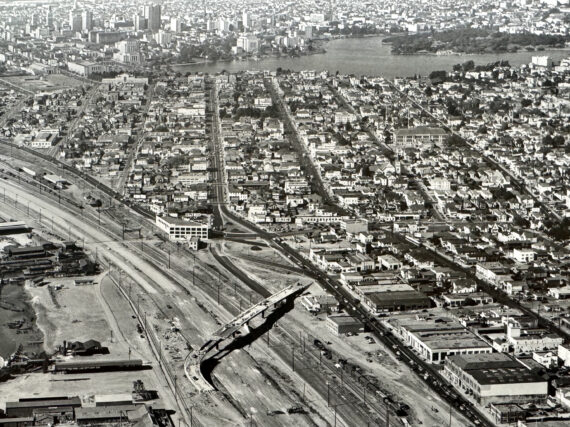

“This was one of the most startling photos in the collection. It says a lot to me about how thoroughly the people involved in this really thought the best thing they could do for downtown Oakland was to smash it with a wrecking ball.”

“Something that you don’t really see in this photo that you see in some of the other photos from this series are the people holding balloons. It looks like a festival or a fair. There are a lot of children… it’s a celebration. ‘Let’s get rid of the old.’”

“This photo is documentation of the ORA giving over a check for the construction of Martin Luther King Jr. Elementary School in Oak Center. This photo includes Lillian Love (far left), who became an ORA commissioner in 1966 after co-founding the Oak Center Neighborhood Association in 1963. They’re all posing on the site where the school is to be built.

One of the things that’s stunning to me is how barren the landscape around them is. You can see city hall in the background, so it gives you a sense of where you are. But it really looks like a desert plain, because so much of this neighborhood has been bulldozed and sat vacant for so long. This is something you see a lot in the collection – they photographed buildings to look like they were on these sparse landscapes. I think they did that to make an argument for why they should be torn down.

When I went through this collection the first time, the really interesting thing is that it has the handwritten crop marks of the photographers and people who did the graphic design. You can see how they wanted this picture to be cropped, so that you don’t see all the empty space. I think that’s because they realized that even though that [showing barren landscapes] worked in other instances, that’s not the argument they’re trying to make with this photo. They wanted to crop out the empty space.”

“This is a photo of the groundbreaking for the Acorn Project when they finally had funding in place to build housing on what had been an empty lot for about 5 years. John B. Williams is on his knees holding the sign in place. The older guy hammering it in is is Robert Weaver, who was the first head of the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). He was the first African American in any cabinet position in US government.

This picture says a lot about where people’s sentiments were when they started the development of what became one of the most infamous housing projects in Oakland. They’re laughing, they’ve got their mouths open with excitement. It’s interesting to look at John Williams and Robert Weaver, two African American officials. One is the head of a city department, one is the first Black cabinet member. There’s a very complicated history behind urban renewal projects that also has to do with African Americans having power at different levels of government for the first time. I feel like one of the reasons why they’ve disappeared in many ways from history is because the outcomes of the programs they ran were not great.

This is right before the era of the first black mayors. [During the 1970s,] there was this whole wave of first time Black mayors in cities who were up against incredible challenges and in many ways were looked at as failures, but they were just put in incredibly impossible situations. This photo has a hyper-local and also national symbolism to it.”

“I’ve spent 20 years in the neighborhood and three years looking at these photos… so it was exciting to find a picture [in the ORA collection] that has a really good shot of my house.”

If you can afford to support East Bay Yesterday, any donation would be greatly appreciated.