Last spring, I started leading historical tours of San Francisco Bay aboard the Pacific Pearl, a fishing boat based in Emeryville. The route covers Berkeley and Oakland, as well as Treasure and Yerba Buena Islands. This fall, I added a second route, which explores the area between Albany Bulb and Point San Pablo in Richmond. This concept was launched on a whim, but the response has been overwhelming. Every one of the tours sold out quickly and I’ve made many new friends on the water.

Spending so much viewing the East Bay from this aquatic perspective has changed the way I think about the place I call home. Instead of simply announcing the first batch of tour dates for the 2020 schedule, I wanted to share some reflections on the previous season.

The following essay was inspired not only by the history and stunning beauty of the Bay, but also by the hundreds of people who have accompanied me over the past few months. I’m not usually the type of person who likes to do the same thing over and over again, but the conversations that take place amidst the wind and salty spray have made each trip unique, enlightening, and incredibly fun. I’m truly looking forward to another round of tours and I hope you can join me. As you’ll find out below, you never know what we’ll see out there…

When humans first arrived in California, the San Francisco Bay didn’t exist. During the tail end of the last ice age, it was a river valley that converged in a waterfall that existed where the Golden Gate Bridge now stands. As recently as 18,000 years ago, the coast of the Pacific Ocean was out past the Farallon Islands, nearly 30 miles west of its current location. Although the Bay appears permanent, this body of water and everything that surrounds it is temporary. The Bay’s presence has been a defining factor in the lives of millions of people who have lived along its shoreline for millenia, but from the perspective of geological time, its existence will be a mere blip.

Since conceptualizing the passage of decades, let alone eons, can be mind-boggling, visual metaphors are helpful. This is why I start tours with a jaunt along Berkeley’s pier. The structure reached 3.5 miles into the Bay when it opened in 1929, making it one of California’s longest piers. The construction of the Bay Bridge in 1936 quickly put the car ferry service that the pier was built to serve out of business and it’s been disintegrating ever since.

On tours, the boat first approaches the section of the pier that had been open to pedestrians up until 2015, when an inspection revealed crumbling concrete and corroded rebar. This span, which is closest to the mainland, is still relatively intact, but as the boat turns west and begins a parallel cruise alongside the structure, we witness the increasing effects of decay. As we push further out, the barnacle-encrusted pillars become more decrepit and feeble. By the time we veer south towards Treasure Island, support beams that were once strong enough to support a gridlocked procession of cars appear barely to exist, like thin ghosts enshrouded in mist. At least above the surface…

Below the surface, these remnants of a failed business venture are teeming with life. As a piece of profitable infrastructure, the pier was obsolete almost immediately, but its sturdy legs have been a boon for undersea creatures that have been living, eating, and breeding amongst this artificial habitat for nearly a century. The feast continues above the waterline, as well. On the first scouting mission to scope out locations, we spotted an osprey perched on one of the guano-covered pylons, ripping the entrails out of a rat.

This all-you-can-eat buffet was almost closed during the middle of last century by a proposal to fill much of the Bay in order to create new property for development. With astonishing hubris, the man who The Reber Plan was named after called the Bay “a geographic mistake” that was interfering with the region’s economic potential. This catastrophic threat famously galvanized the three Berkeley women who co-founded Save the Bay. These activists not only helped end a century-long trend of infill projects by pushing for stricter regulation, but reframed widespread perception of the Bay from a pollution-choked industrial thoroughfare to a sublime, delicate, and complex ecosystem.

I was having trouble understanding how the Bay’s beauty could ever have been ignored until I saw this quote from Lucretia Edwards, an influential activist, explaining that when she moved to Richmond in 1948, only 67 feet out of the city’s 32 miles offered public access. “I was enraged. You hardly knew that the Bay was there,” she said. Over the next five decades, Edwards channelled her rage into an obsession that helped transform thousands of shorefront acres into parks.

Considering the global trajectory towards widespread cataclysm (ocean acidification, deforestation, melting tundra, etc.), the Bay’s revival since its World War II-era nadir as a dumping ground for the military’s radioactive waste has been a beacon of hope. For the most part, environmental concerns have triumphed over business prerogatives. Some even consider the combined efforts to re-establish wetlands and marshes throughout the Bay as “the largest-scale coordinated habitat restoration effort in the world.” Whenever a rare heatwave hits and I visit Alameda’s Crown Beach for a swim, I find myself grateful that the Bay is no longer known as “The Big Stench,” a nickname coined during days before sewage treatment plants.

One particularly exciting example of the Bay’s recovery is the return of harbor porpoises following a decades-long absence. Their population had been decreasing since the Gold Rush era, when hydraulic mining flushed millions of tons of rocks, soil and toxic byproducts out of the Sierra Nevada, to the detriment of everything living downstream. The rise of refineries, shipyards, and factories along the perimeter of the Bay and near-total eradication of wetlands made turned the porpoises’ formerly pristine world into a poisonous cesspool . Whatever pods remained until the early 1940s were likely driven away by the mass militarization of the Bay during the leadup to World War II.

Due to fears of Japanese invasion, the Navy planted more than 600 underwater mines near the Golden Gate and stretched a giant steel net all the way from Sausalito to San Francisco’s Fort Mason just in case any submarines managed to dodge all those explosives. The underwater noise created by the massive cables being dragged back and forth by the Bay’s ceaseless currents would have had a devastating effect on porpoises’ ability to communicate and locate prey. (Other marine mammals faced much worse than sonic interference. According to the National Park Service: “Navy blimps armed with depth charges patrolled offshore waters searching for Japanese submarines but only attacked the occasional unfortunate whale.”)

In any case, decreased pollution, demilitarization, and a ban on gill nets have all contributed to porpoises returning in greater numbers to the Bay in recent years. The elusive cetaceans are smaller and more shy than dolphins, so I was thrilled to see three of them swimming just offshore from the Craneway Pavilion a few weeks ago while I was riding my bike along Richmond’s shoreline during another scouting mission. The harbor that hundreds of warships had once poured out of was so calm that the sound of the light breeze was broken only by squawking gulls and voracious pelicans splashing headfirst into the dark blue water.

On my tours, I say that “the future could look like the past” because of all the progress that’s currently being made to restore oyster beds, patches of native cordgrass, and other features that defined the liminal zone between land and water before colonization ushered in an era when these boundaries became much more stark. I sprinkle in these positive stories of ecological restoration to counterbalance the overwhelming dread that comes with the realization that much of what we view during these trips could be submerged well within the next century. It makes me shudder, but sometimes I can’t stop thinking about a distant future when the Port of Oakland’s iconic cranes will barely peek out above the lapping waves, their rusty masts enshrouded in mist.

To paraphrase Heraclitus, you never go into the same Bay twice. I’ve been in a few dozen Bays this past year, even though the boat always left from the same dock. The purpose of each of these tours has been to share history, but it’s the incremental changes of the present that remain lingering in my mind. The steady rise of new buildings in Brooklyn Basin, the transition of Brooks Island from green to golden, the osprey nests that were abandoned for the winter once September arrived.

I’m looking forward to watching a new cycle unfold next year, and while the routes I travel will be the same, so much will be different, as we push forward into the mist, time and time again.

-Liam O’Donoghue

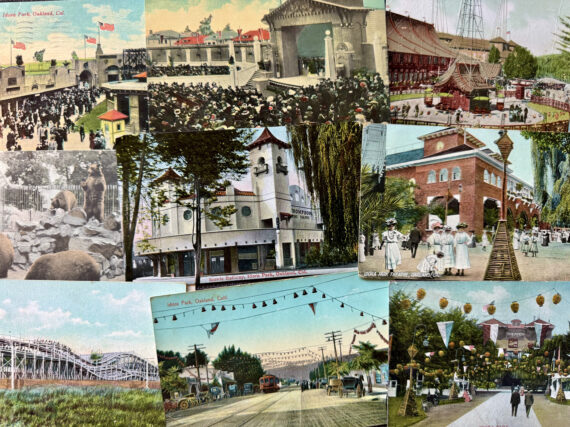

Click here for tickets to East Bay Yesterday’s 2020 historical boat tours. Please note that the February and March dates are the Richmond tour and the April dates are the Oakland tour. I’ll be announcing more Oakland dates for within the next few weeks. To hear stories regarding the photos below, come on one of the tours…